Exploiting linearity of $\mathbb E$: Buffon's Noodle

Introduction

In a normal treatment of probability theory, one of the first properties of taking expectation $\mathbb E$ is linearity: $$ \mathbb E[X + Y] = \mathbb E[X] + \mathbb E[Y]. $$

Though it is a pretty unassuming property for most students, it is actually a very useful and interesting property. A common use case is for problems where the different RV’s are “obviously” independent.

Example 1: Sum of two dice

Suppose we have two dice. We can denote their pip values as $X_1,X_2$ and then note $$\mathbb E[X_1+X_2] = \mathbb E[X_1] + \mathbb E[X_2] = 2\cdot 3.5 = 7. $$

But are there any more striking examples of using linearity of expectation? Yes – a classical problem(s) known as Buffon’s {Needle | Noodle}, with the latter being a short generalization of the former. We will first solve the Needle problem using usual probability theory, before providing a generalized result using expectation.

Buffon’s Needle

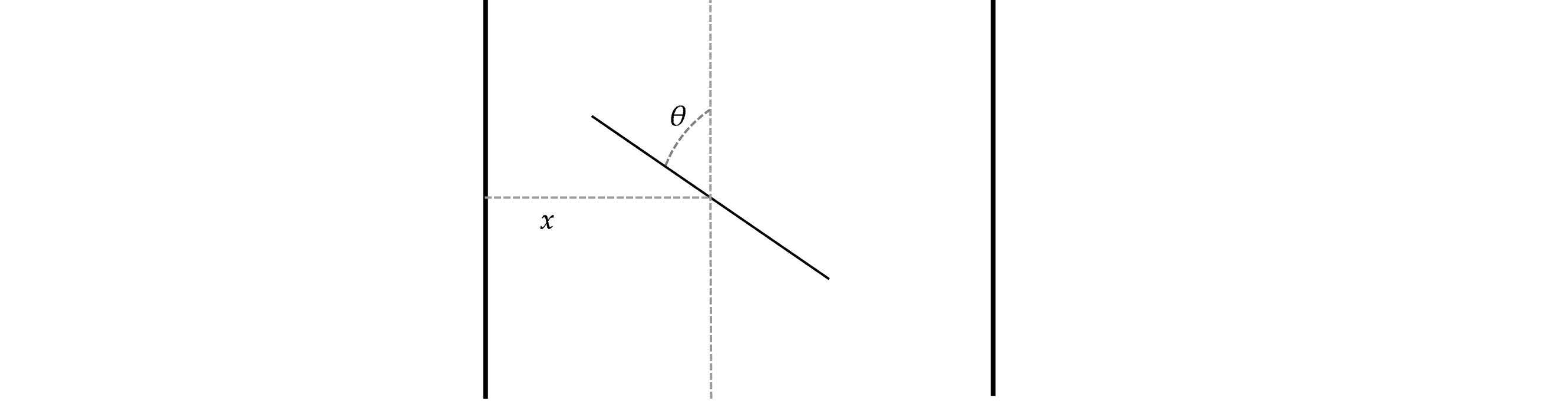

The problem statement is as follows: if we have a plane consisting of evenly spaced parallel lines (in one axis), if we have a randomly place line segment of length $\ell$ on the plane, what the probability that the segment intersects one of the lines? A more real-to-life statement often involves a wooden plank floor and the probability a needle (hence the name) intersects the border of two planes. To solve this problem, we first setup a couple of variables. We can denote $x$ as the distance from the center of the line segment to the nearest vertical line segment (where we use the usual notion of point-line distance). Then we can denote $\theta$ as the acute angle formed between the line segment and the vertical line axis.

Diagram of setup variables

Since the distance $x$ can vary from $0$ to $d$, where $d$ denotes the intervals between vertical lines, and clearly the distribution is uniform, we can conclude $$ f_x(t) = \frac{1}{d/2} = 2/d, \qquad t\in[0, d/2] $$ where $f_x$ denotes the PDF of $x$. In a similar fashion, we can write $$ f_{\theta}(t) = 2/\pi, \qquad t\in[0, \pi/2]. $$ We can note that then the needle crosses a vertical line if $$ x \leq \frac\ell 2 \sin(\theta). $$ From here, we take two cases.

[Short Needle]. Suppose $\ell \leq d$. Thus with probability 1, the needle will only cross a single vertical line, if any. Then we can write the probability of crossing $$ \begin{align*} P &= \int_{[0,d/2]\times [0,\pi/2]}f_{x,\theta}(x,\theta) \bm 1_{\{ x \leq \frac\ell 2 \sin(\theta)\}} \diff (x,\theta)\\ &=\int_{\theta=0}^{\pi/2}\int_{x=0}^{(\ell/2)\sin(\theta)} f_x(x) f_\theta(\theta) \diff x \diff \theta \\ &=\int_{\theta=0}^{\pi/2}\int_{x=0}^{(\ell/2)\sin(\theta)} \frac{4}{d\pi} \diff x \diff \theta \\ &= \frac{2l}{d\pi}. \end{align*} $$

[Long Needle]. In this case, we must take into consideration the cases where the needle is long enough to gurantee crossing a vertical line. In particular, if the horizontal component of the needle is longer than $d$, we know the needle is guranteed to cross a vertical line. That is, we know the needle will cross with probability 1 if $$ \ell \sin(\theta) \geq d $$ or $$ \theta \geq \arcsin(d/\ell). $$ Otherwise, we can note that the answer is the same as the short case. Therefore, $$ \begin{align*} P &= \int_{\theta=0}^{\arcsin(d/\ell)} \int_{x=0}^{(\ell/2)\sin(\theta)} \frac{4}{d\pi} \diff x \diff\theta + \frac2\pi\left({\frac\pi 2 - \arcsin(d/\ell)}\right) \\ &= \frac{2\ell}{d\pi} \left(1- \cos(\arcsin(d/\ell))\right) - \frac2\pi\arcsin(d/\ell) + 1\\ &=\frac{2\ell}{d\pi} \left(1- \frac{\sqrt{\ell^2-d^2}}{\ell}\right) - \frac2\pi\arcsin(d/\ell) + 1. \end{align*} $$

Buffon’s Noodle

The aptly named Buffon’s Noodle problem deals with a generalization of the needle problem – what we consider a “noodle” instead of a needle? In technical terms, we consider a smooth (reasonably well-behaved) continuous random curve. In this case, the probability distribution depends on the curve, but (critically) the expected value of the number of crossings does not. We will go through the rough proof here (a more detailed treatment can be found in Klain & Rota).

We first consider a piecewise linear curve (i.e. polygonal), consisting of say $n$ line segments. In particular, we can control $n$ to make the line segments as small as we want (since if the line segments are too long, we can break them up into consecutive smaller segments). So for individual length small enough, each segment can only have at most one crossing. Denote $X_1,\dots,X_n$ as the indicator RV’s of crossing for each segment. Then $$ \mathbb E[X_1+\dots + X_n] = \mathbb E[X_1] + \dots + \mathbb E[X_n] \tag{1} $$

denotes the expected total number of crossings of the polygonal curve. From the definition of indicators, we can know that $\mathbb E[X_k] = \mathbb P \{\text{segment $k$ has a crossing}\}$. We can conclude here easily with our previous result on the needle; but we shan’t and proceed in a different manner.

We can easily observe $\mathbb E[X_k] = f(L_k)$ where $L_k$ is the length of the linear segment. Then from (1) we can get that $f(L_1 + L_2) = f(L_1) + f(L_2)$ i.e. $f$ is a linear transformation $\mathbb \R\to\mathbb\R$. We can write $$ f(L) = c L $$ with $c$ a constant to be determined. We can determine $c$ with a useful curve of our choice. In particular, we can choose a circle $S$ with radius $d/2$, which will almost surely intersect two vertical lines. Thus $$ \mathbb E[S_{\text{crossings}}] = 2. $$ meanwhile the length of the curve is $\pi d$. Thus $$ f(\pi d) = c\pi d =2; \qquad c=\frac{2}{\pi d} $$ and thus we can conclude $$ \mathbb E[\text{crossings}] = \frac{2L}{\pi d}. $$

where $L$ is the length of the curve. We can verify this agrees with the needle case solved above.